TOFWERK, Thun, Switzerland

Wyon, Appenzell Steinegg, Switzerland

This whitepaper introduces a novel leak detection method for batteries based on proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PTR-TOFMS), developed in collaboration between Wyon and TOFWERK. This method directly detects electrolyte solvent emissions under ambient conditions, enabling real-time, quantitative leak testing of individual battery cells with unprecedented sensitivity down to 10-12 mbar L s-1 and measurement speed below 60 seconds.

Need for a Novel Leak Detection Method for Batteries

In the medical device industry, quality control is paramount. From active implants to wearable diagnostics, the hermetic integrity of micro-batteries is crucial to ensure both performance and patient safety. Traditional leak detection methods for batteries – such as helium bombing, gravimetric mass loss, vacuum pressure decay, and bubble testing – have long been used to assess battery hermeticity. However, each method presents significant limitations, summarized in the next chapter.

Compared to conventional methods, PTR-TOFMS offers superior sensitivity for ultra small leaks, rapid throughput – testing in seconds per cell – non-destructive testing under ambient pressure, compatibility with polymer housings and micro-batteries, and quantitative, traceable results for robust quality assurance. This method is especially suited for medical device manufacturers who must meet the most stringent regulatory and quality assurance standards. It enables individual cell-level testing, ensuring that every battery meets the highest reliability criteria before integration into critical medical systems.

PTR-TOFMS can detect carbonate leak rates down to 10-12 mbar l s-1 quantified at ambient conditions in real time. Carbonate solvents, a component of lithium-ion battery electrolytes, are detected directly – without the need for a tracer gas like helium. This direct detection eliminates false positives. We demonstrate the robustness of this method by testing around 400 batteries. Finally, the relative merits of the new method are compared to the benchmark helium bombing leak detection method.

Overview of Current Methods and their Limitations

A wide range of leak detection methods are used in battery production and quality control. Each method has specific strengths and limitations on the required sensitivity, material compatibility, production throughput, and ambient conditions. Table 1 summarizes the most relevant techniques for leak detection/hermiticity testing of medical micro-batteries.

Helium bombing is a well-established method with excellent sensitivity (down to 10-12 mbar L s-1), but it requires vacuum chambers, helium infrastructure, and long dwell times of several minutes per sample, slowing down the throughput. Moreover, polymer housings can lead to false positives due to helium permeability [1], [2]. Samples with a cavity volume smaller than approximately 0.5 cm3 are impractical to test within reasonable timeframes using standard helium bombing setups, due to limited helium accumulation and rapid diffusion losses [3].

Gravimetric analysis and vacuum pressure decay detect mass loss, respectively pressure loss over time. Mass/pressure losses from small leaks, however, need to be tracked over long periods of time. For instance, it takes >1000 years for 1 cm3 of gas to escape a leak with a leakage rate of 10-11 mbar L s-1 [4]. Neither technique is suitable for high-throughput applications.

Bubble tests are the most basic form of leak detection in batteries, relying on visual observation of gas bubbles in a liquid bath. They are non-quantitative, operator-dependent, and not applicable for miniaturized systems. The summarized disadvantages of established leak testing methods triggered the need for an alternative method. The PTR-TOFMS as a novel leak detection method for batteries is presented in the next chapter.

| Method | Sensitivity (Leak Rate, mbar L s -1) | Material Compatibility | Throughput (Time per Battery, min) | Suitability for Medical Micro-Batteries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTR-TOFMS | 10-6 – 10 -12 | Excellent (works with polymers and micro-structures) | <1 | Excellent (precise, scalable, ambient conditions) |

| Helium Bombing | 10-6 – 10 -12 | Limited (issues with polymers) | 5 – 30 | Limited (false positives, He-infrastructure & vacuum required) |

| Gravimetric Analysis | 10-6 – 10 -8 | Broad | Hours to days | Limited (slow, not specific) |

| Vacuum Pressure Decay | 10-3 – 10 -6 | Broad | 1 – 5 | Moderate (not sensitive) |

| Bubble Test | >10-3 | Limited (requires immersion and visibility) | 1 – 5 | Poor (not scalable or sensitive) |

Novel PTR-TOFMS Leak Rate Method

A Vocus 2R CI-TOF with PTR Reactor (Figure 1) from TOFWERK is used for hermeticity testing of Wyon batteries. The instrument has been equipped with a manual measurement chamber for batteries.

The novel leak rate method has two major steps:

- Battery pretreatment (cleaning and tempering)

- PTR-TOFMS quantification of battery leak rates (Figure 2)

Battery pretreatment

Reliable and reproducible hermiticity testing requires careful pretreatment, which consist of two essential steps: (i) cleaning and (ii) thermal equilibration at elevated temperatures. Since the PTR-TOFMS detector cannot distinguish between emissions from a leaking battery and those from surface contamination, the accuracy of the test critically depends on the cleanliness of the battery surface.

During electrolyte filling, small amounts of electrolyte spill and contaminate the battery casing. Additionally, during cell sealing and formation, electrolyte residues may become trapped in narrow gaps or under structural elements such as feedthroughs.

The cleaning process itself includes two stages: A primary cleaning and a thermal evaporation step to remove residual solvents. At Wyon, primary cleaning is performed either by CO2 snow blasting or by immersion in ultrasonic baths using suitable solvents such as ethanol. Any remaining electrolyte residues that cannot be removed mechanically or chemically are subsequently evaporated thermally. This thermal step is carried out at 50 °C for more than 2 hours (after CO2 cleaning) or for more than 4 hours (after solvent cleaning). These temperatures are well above the melting point of typical lithium-ion battery solvents, yet gentle enough to avoid damaging the battery.

Beyond its cleaning effect, thermal equilibration plays a crucial role in enhancing both the sensitivity and reproducibility of the leak detection test for batteries. Since leak rates increase exponentially with temperature due to increased vapor pressure of the solvents and inner gas pressure inside the battery, elevated temperatures improve the detectability of ultra-small leaks. At the same time, maintaining a stable temperature minimizes measurement variability, as temperature fluctuations significantly affect the consistency of the measured leak rates.

PTR-TOFMS Quantification of Battery Emissions

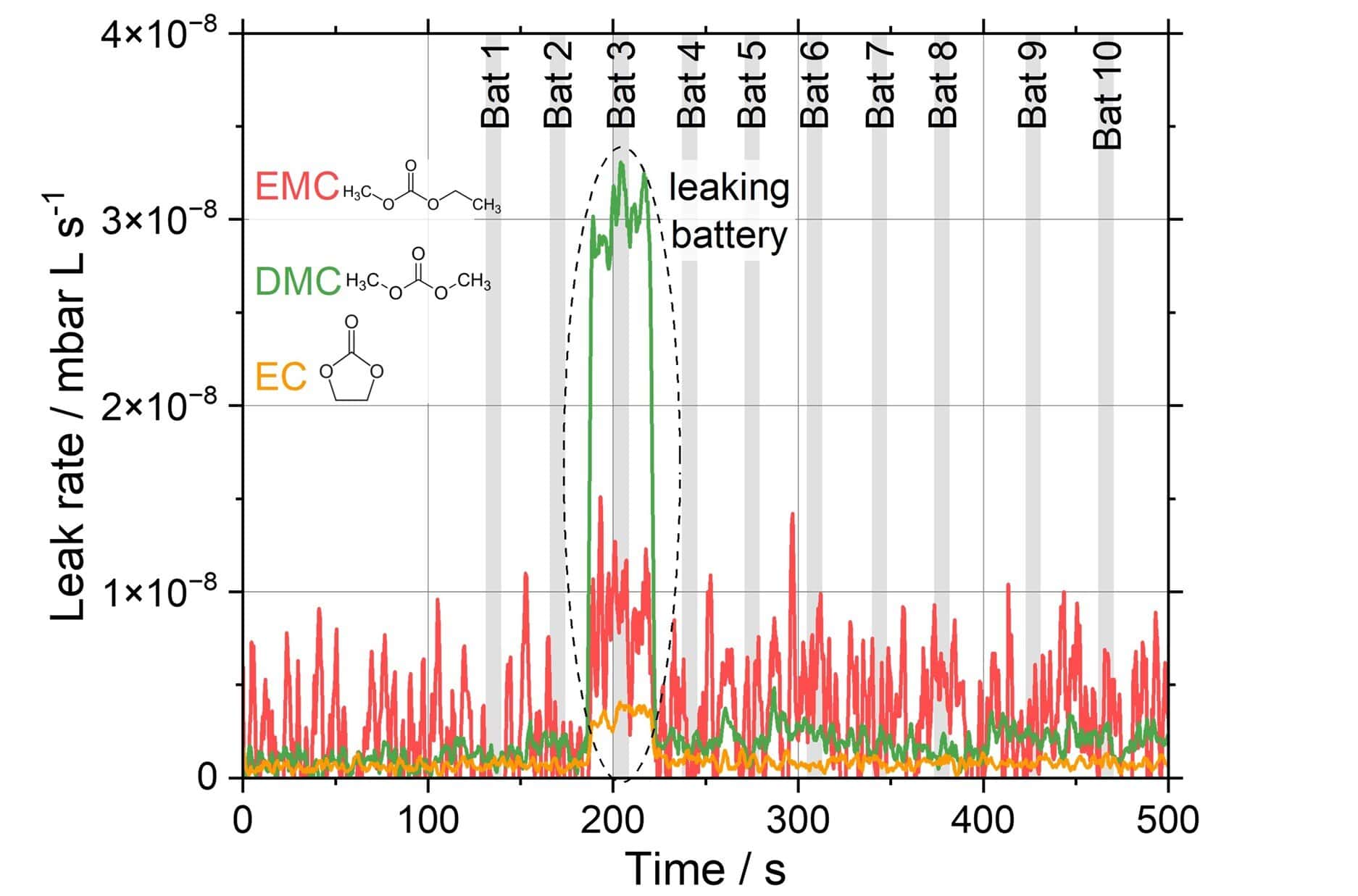

To illustrate how the leak rate measurement is conducted, an exemplary hermeticity test of ten batteries with a metal casing is shown (Figure 3). The battery electrolyte is composed of three solvents: Ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC), dimethyl carbonate (DMC), and ethylene carbonate (EC). The life signal of the solvent leak rates is averaged for each battery during the time indicated by the grey bars. The battery “Bat 3” is identified as leaking with an increased solvent leak rate compared to the other batteries. This demonstrates how effective and fast (below 10 minutes) 10 batteries can be tested in a row under ambient conditions.

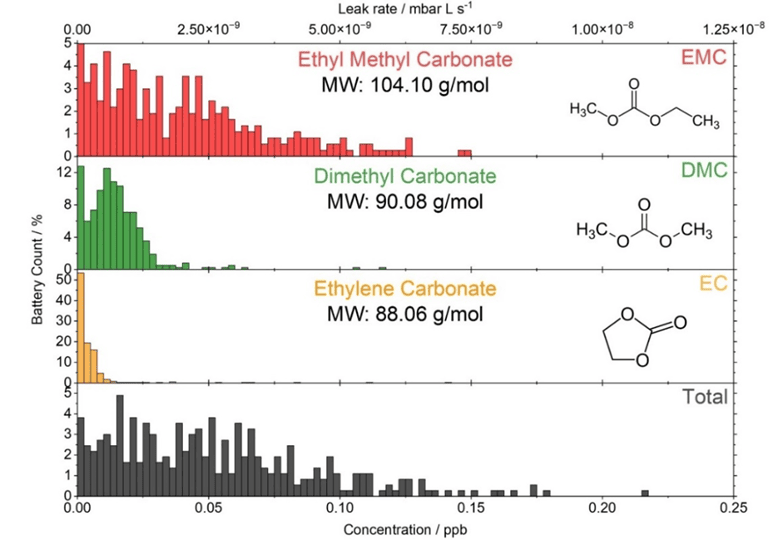

In a battery OEM different types of batteries are present and must be tested. Depending on the battery type, the sealing, the casing material, the electrolyte composition, etc., different solvent leak rates are detected. This is outlined by the statistical PTR-MSTOF data obtained from around 400 batteries with a metal casing (Figure 4). The leak rate level that can be considered as hermetically sealed must be defined between OEM and customer or by the regulators.

The MIL-STD-883 standard defines a threshold for leaking systems that exceed a helium leak rate of 5 x 10-8 mbar L s-1 [5]. According to equation (2), this corresponds to 1 x 10-8 mbar L s-1 for the carbonates used in our case (see chapter Theoretical Background of Hermeticity Testing for more details). The measured leak rates (Figure 4) for the carbonate solvents of the battery electrolyte are typically below this threshold. The sum of all solvents is shown as the “total” emission of this specific battery type.

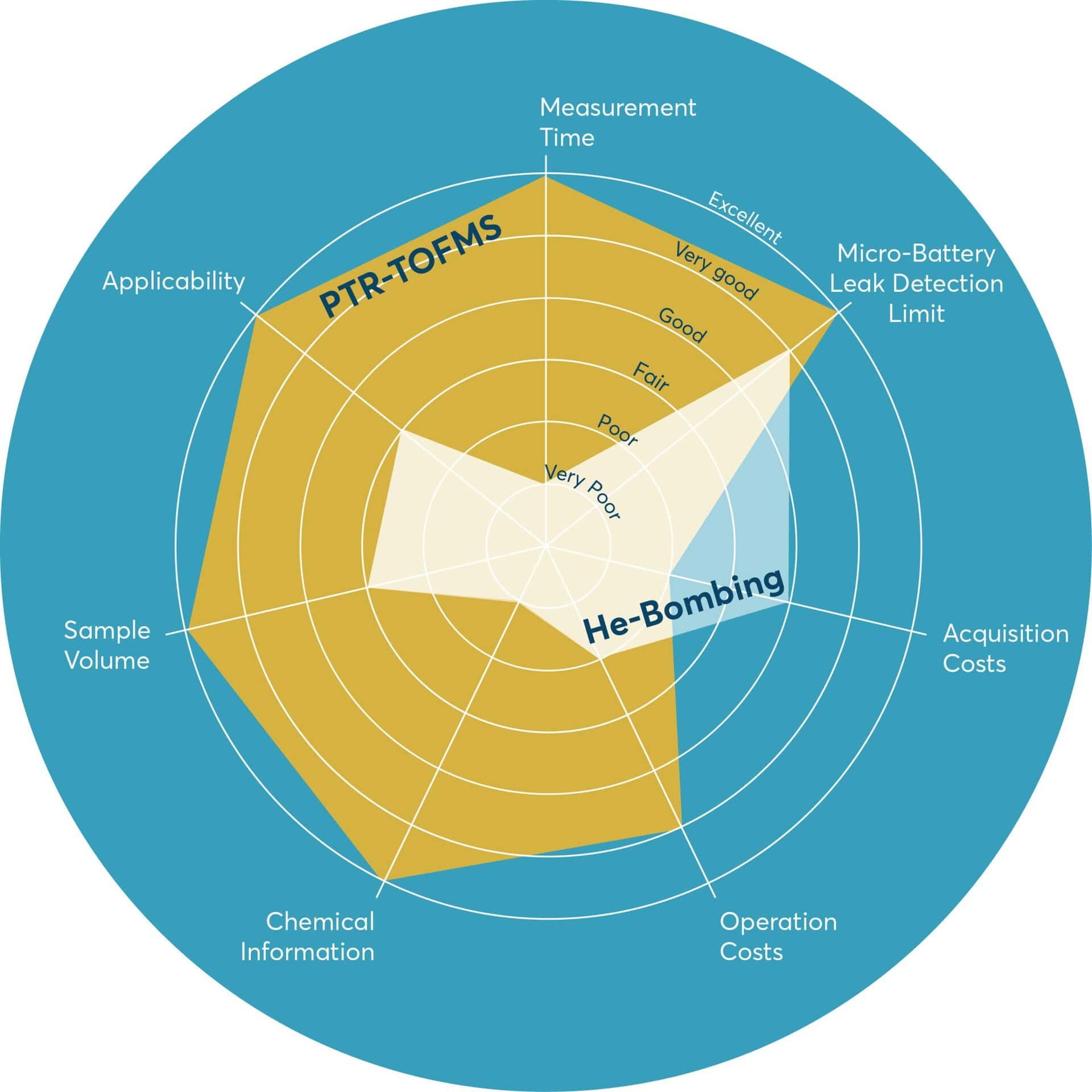

Comparison of PTR-TOFMS to Helium Bombing

Helium bombing is a well-established leak detection method that offers excellent sensitivity, with detection limits down to 10-12 mar L s-1. It is widely used in the electronics and aerospace industries and is based on the principle of tracer gas accumulation and subsequent detection via mass spectrometry. However, when applied to medical micro-batteries or implants, helium bombing presents several limitations that PTR-TOFMS effectively addresses.

1. Sensitivity

Both helium bombing and PTR-TOFMS achieve comparable sensitivity, with detection limits reaching 10-12 mbar L s-1 (further details in the section “Limit of Detection”). However, PTR-TOFMS directly detects electrolyte solvent emissions, providing chemical specificity that helium bombing lacks. Furthermore, because PTR-TOFMS directly detects electrolyte solvent molecules, any detected signal must originate from the battery itself (leak or surface contamination), effectively eliminating false positives when the battery was properly cleaned.

2. Test Time

Helium bombing typically requires 5-30 minutes per battery due to the need for helium pressurization and dwell time. In contrast, PTR-TOFMS enables real-time detection with measurement times less than 1 minute in a manual process and less than 3 s in a fully automated process (not established yet), significantly improving throughput.

3. Cost and Infrastructure

Helium bombing requires helium supply and vacuum systems. These systems are costly, complex, and require regular maintenance. PTR-TOFMS, while having higher initial acquisition costs, operates under ambient pressure without tracer gases, significantly reducing operational complexity and consumable costs. Over time, the lower maintenance requirements and higher throughput of PTR-TOFMS result in a more cost-effective solution for high-volume or high-reliability production environments. It should be noted that both methods require regular calibration using similarly sophisticated procedures, which contributes comparably to operational costs.

4. Material Compatibility

Helium can permeate polymer housings, leading to false positives in helium bombing tests [1], [2]. PTR-TOFMS is compatible with polymer-encased batteries, implants and microstructures, making it more suitable for modern battery designs used in medical applications.

5. Suitability for Medical Micro-Batteries

Medical micro-batteries demand high reliability and individual cell-level testing. PTR-TOFMS supports non-destructive, high-throughput testing with quantitative results, making it ideal for quality assurance in medical device manufacturing. Helium bombing, while sensitive, is less practical for small-scale (<0.5 cm3), polymer-based batteries due to its limitations in compatibility and throughput.

The sensitivity of helium bombing decreases with shrinking internal volume. According to the Howl-Mann equation, smaller cavities accumulate less helium during pressurization, resulting in weaker signals during detection. Consequently, the minimum detectable leak rate increases for smaller batteries. For example, to detect a leak rate of 10-12 mbar l s-1 with 30 minutes helium exposure, 5 minutes dwell time, and 5 bar helium pressure, the internal volume must be larger than 0.1 cm3 [7].

Thus, batteries with cavity volumes smaller than 0.5 cm3 become increasingly difficult to measure, as the measurable signal strength of helium-bombing decreases exponentially with decreasing volume, even under elevated helium pressure and extended dwell times [8]. PTR-TOFMS, by contrast, directly detects VOC emissions under ambient conditions and remains fully sensitive even for micro batteries with minimal internal volume.

In summary, while helium bombing remains a benchmark method in leak detection, PTR-TOFMS offers a more efficient, versatile, and application-specific solution for the stringent requirements of medical micro-battery testing. These advantages are visually summarized in a radar plot (Figure 5). It highlights the superior performance of PTR-TOFMS across key criteria including sensitivity, test time, infrastructure simplicity, material compatibility, and cost efficiency.

Summary & Conclusions

This white paper introduces a novel approach to leak detection in lithium-ion batteries for medical applications using real-time PTR-TOFMS analysis. The method is designed to overcome the limitations of traditional helium bombing, particularly in applications requiring high sensitivity, fast throughput, and compatibility with polymer-based or micro-scale battery designs. The method enables real–time detection of electrolyte solvents under ambient conditions, achieving leak rate detection limits down to 10–12 mbar L s-1 with measurement times of a few seconds per battery. This makes it especially suitable for high-reliability sectors, such as rechargeable batteries for medical devices and implants, where individual battery cell testing is critical.

The sensitivity of the PTR-TOFMS method is adjustable, allowing it to be tailored to the specific requirements of the application. Implantable batteries may require maximum sensitivity to detect even the smallest leaks, which can be achieved by extending the measurement time and reducing the purge flow. For less critical applications, such as batteries used in non-medical devices, the sensitivity can be reduced to enable faster measurement and higher throughput. This flexibility makes PTR-TOFMS not only precise, but also scalable and adaptable to a wide range of production and quality assurance environments.

Looking Ahead: Potential Use Cases

While this white paper focuses on leak testing of medical micro-batteries, the potential applications of PTR-TOFMS extend far beyond. The method can be adapted for testing entire medical devices, such as implants that contain integrated batteries, as well as non-medical systems where hermetic sealing is critical. With minor modifications, PTR-TOFMS can be applied to any sealed device or packaging – from pharmaceutical containers to electronic modules – provided that a detectable tracer molecule is present inside the enclosure. This tracer can either be naturally occurring (e.g., residual solvents or volatiles) or intentionally introduced, such as ethanol or other volatile markers. This flexibility opens the door to a wide range of industrial and biomedical leak testing scenarios, all benefiting from the method’s high sensitivity, speed, and compatibility with ambient conditions.

Moreover, the potential of PTR-TOFMS extends even further when considering automation. By integrating automated sample handling and measurement routines, the overall test cycle time can be significantly reduced to less than 3 seconds per sample. This enables faster transitions between samples and minimizes manual intervention, thereby increasing measurement throughput. Such automation makes PTR-TOFMS highly scalable for industrial applications, including high-volume production environments where rapid and reliable leak testing is essential.

Appendix

Theoretical Background of Hermeticity Testing

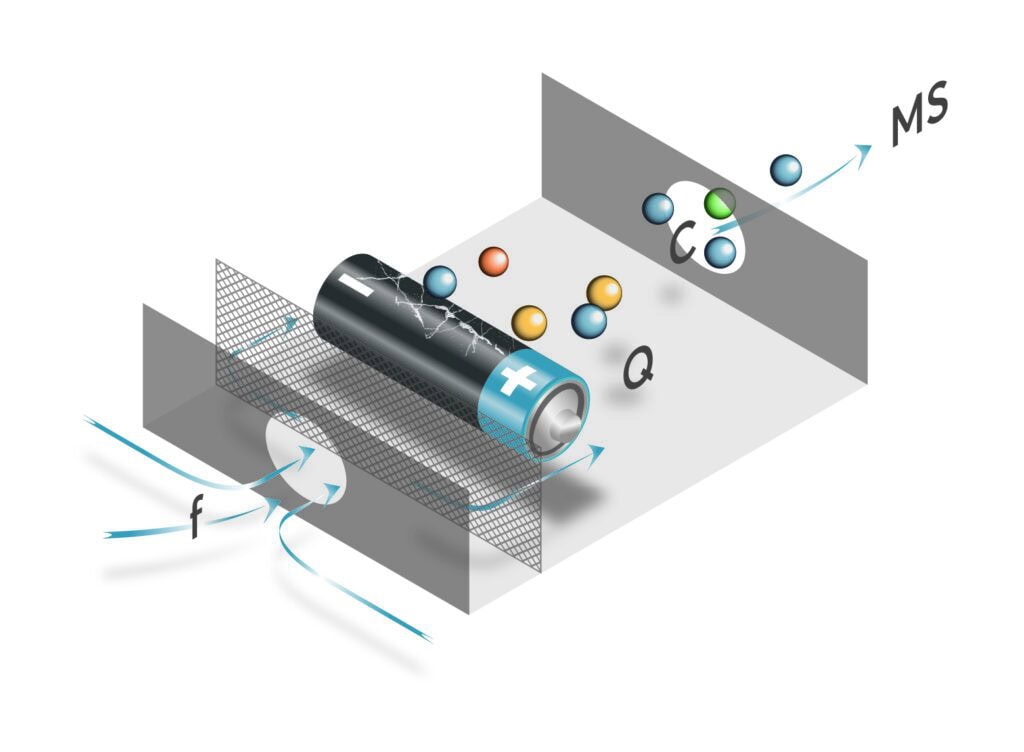

For the hermeticity testing, the cleaned and thermally equilibrated batteries are placed into a measurement chamber heated to 50 °C. This chamber is continuously purged with a VOC-free carrier gas, such as high purity nitrogen or a catalytically purified air. In our setup, ambient lab air is purified by passing it through a platinum mesh heated to 400 °C, effectively removing volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

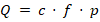

The purge gas flows through the chamber at a defined rate f (in sccm), collecting any electrolyte solvent vapors emitted by the battery. These vapors are transported to the mass spectrometer, where their concentration c (in ppb) is measured [3, 4] . The leak rate Q (in mbar L s-1) is then calculated using the following relation [4] (1):

where p is the pressure inside the measurement chamber (typically 1000 mbar). For example, a measured concentration of 0.1 ppb at a purge flow of 3000 sscm corresponds to a leak rate of 5 x 10-9 mbar L s-1.

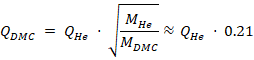

To compare leak rates of different gases, Knudsen diffusion must be considered [5]. The leak rate is inversely proportional to the square root of the molar mass M of the gas. For instance, the leak rate of the solvent DMC relative to helium can be approximated as (2):

Thus, carbonate leak rates (e.g., EMC, DMC and EC) are typically about 20% of the equivalent helium leak rate.

Principle of PTR and TOFMS for Leakage Quantification

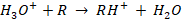

Organic solvent molecules R are ionized via proton transfer reaction (PTR) using protonated water H3O+ clusters:

The reaction occurs if the proton affinity of R exceeds that of water (691 kJ mol-1). For example, ethanol (776 kJ mol-1) readily accepts a proton from H3O+, forming a positively charged ion RH+ [10].

These protonated solvent molecules are then accelerated in an electric field and separated by time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOFMS). Their velocity depends on their mass-to-charge ratio and the applied acceleration voltage U. The time required to traverse the flight path is given by (3)

where q is the electric charge and mRH+ the mass of the ion. Molecules of different masses thus arrive at the detector at different times, allowing for their separation and identification.

The signal intensity in the mass spectrometer is directly proportional to the concentration of the emitted solvent, and therefore to the leak rate of the battery. This enables real-time, quantitative leak detection with high chemical specificity.

Limit of Detection

Achieving a low limit of detection (LOD) is essential for effective leak detection in batteries, particularly in medical or high-reliability applications. The LOD is defined as LOD = 3 σ [11], where is the standard deviation (noise) of the measured signal. In our setup, the system is optimized for high throughput and fast measurement. With a maximum purge flow of 3000 sccm and a signal accumulation time of 10 seconds, we achieve a noise level of approximately σ ≈ 0.003 ppb. This corresponds to a detection limit of LOD = 0.009 ppb = 4.5 x 10-10 mbar L s-1 with a total measurement time of less than 30 seconds per battery.

The sensitivity can be further increased by reducing the purge flow, which decreases dilution of the emitted solvents. However, this also increases the purging time. The following table (Table 2) illustrates the relationship between concentration, purge rate, measurement time, and resulting leak rate.

| Concentration c / ppb | Purge rate f / cm 3 s -1 | Total measurement time required tmeasurement / s | Corresponding leak rate Q / mbar Ls-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3000 | 25 | 5 x 10 -8 |

| 0.1 | 3000 | 5 x 10 -9 | |

| 0.01 | 3000 | 5 x 10 -10 | |

| 0.001 | 3000 | 5 x 10 -11 | |

| 1 | 100 | 60 | 1.7 x 10 -9 |

| 0.1 | 100 | 1.7 x 10 -10 | |

| 0.01 | 100 | 1.7 x 10 -11 | |

| 0.001 | 100 | 1.7 x 10 -12 |

References

[1] Han, B. (2012). Measurements of true leak rates of MEMS packages. Sensors, 12(3), 3082–3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/s120303082

[2] Vanhoestenberghe, A., & Donaldson, N. (2011). The limits of hermeticity test methods for micropackages. Artificial Organs, 35(3), 242–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01222.x

[3] Pfeiffer Vacuum GmbH. (n.d.). Leak detection know how and solution. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://leak-detection.pfeiffer-vacuum.com/en/leak-detection-know-how

[4] Pfeiffer Vacuum GmbH. (n.d.). Leak detection know how and solution. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://leak-detection.pfeiffer-vacuum.com/en/leak-detection-know-how

[5] Knudsen, M. (1909). Die Gesetze der Molekularströmung und der inneren Reibungsströmung der Gase durch Röhren. Annalen der Physik, 333(1), 75–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19093330106

[6] Bhosale, R. S., et al. (2017). Study on leak testing methods. IJSRD – International Journal for Scientific Research & Development, 5(01), 1618. ISSN (online): 2321-0613.

[7] International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. (2025). Limit of detection. In IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (5th ed., Online version 5.0.0). https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.L03540

[8] United States Department of Defense. (1996, December 31). MIL-STD-883E – Test method standard for microcircuits.

[9] ASTM International. (2022, November 30). ASTM F2391-05(2016) – Standard test method for measuring package and seal integrity using helium as the tracer gas.

[10] Hunter, E. P. L., & Lias, S. G. (1998). Evaluated gas phase basicities and proton affinities of molecules: An update. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 27(3), 413–656. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.556018

[11] International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. (2025). Limit of detection. In IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (5th ed., Online version 5.0.0). https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.L03540